In Defence of the term ‘Post-Internet’

How can we be Post-Internet when internet is still here?

When I think of the term Post-Internet, a series of mental images are conjured;

Corporate logos rippling across mass produced t-shirt fabric, the sickly sweet and penetrative light of LCD screens, grossly perfect stock imagery mimicking a human experience, assemblages of metal and plastic and glass producing an approximation of the real, like a city. When I think of the term Post-Internet, I think of what it feels like to live in a world where I cannot afford to travel due to carnivorous market forces but I can, from the comfort of my home, see the world through 2-dimensional images, have pink synthetic-fur earmuffs from China delivered to my door, befriend people from Turkey through online extremist forums, compile my life into easy access data via the mediation of a loving machine.

This is what it means to be Post-Internet; to live amongst the fallout of hyper-complex communications networks, watching the self-mutate into a million atomised cells and watching the world follow suit, all under the watchful gaze of a planetary machine.

In 2006, artist and curator Marisa Olson coined the term Post-Internet to describe a new critical framework she had observed emerging in young, digitally engaged artists. Throwing off the utopian ideals of their egalitarian and vehemently anti-institutional net.art predecessors (who pioneered the internet and coding as artistic medium), this new wave of net-aware artists engaged with the realities of networked life beyond an exaltation and implementation of innovative technology.

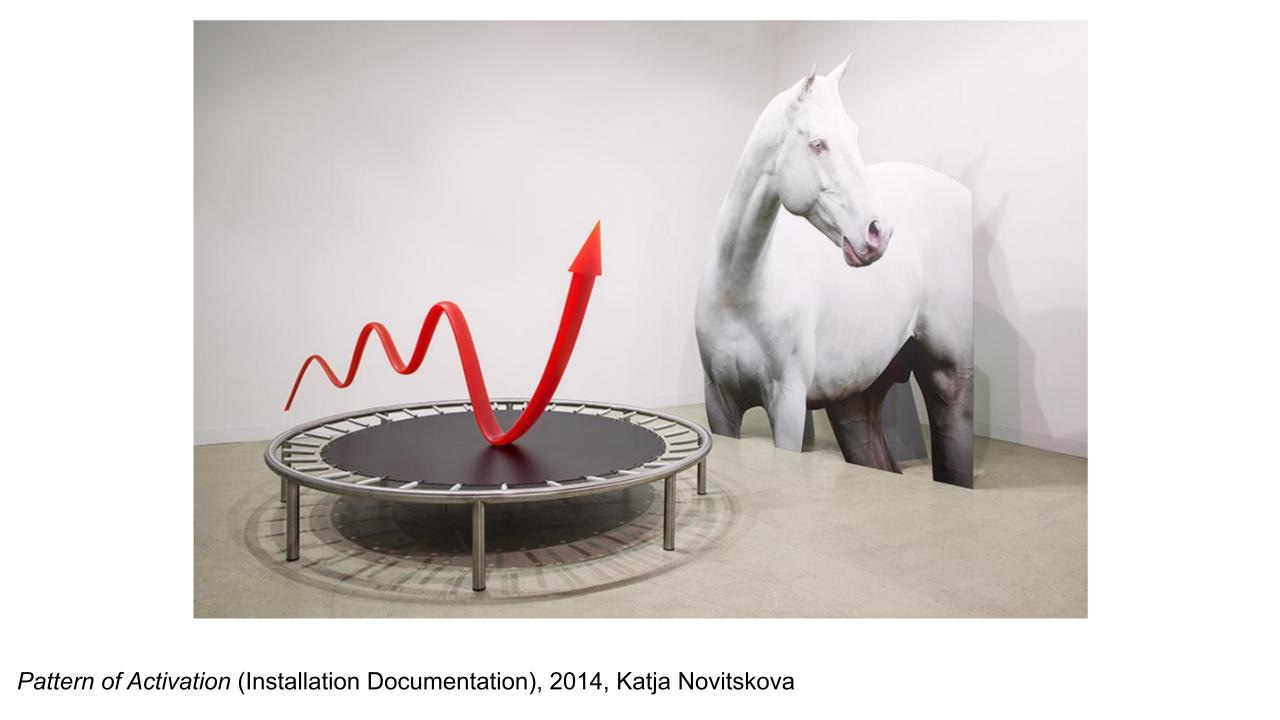

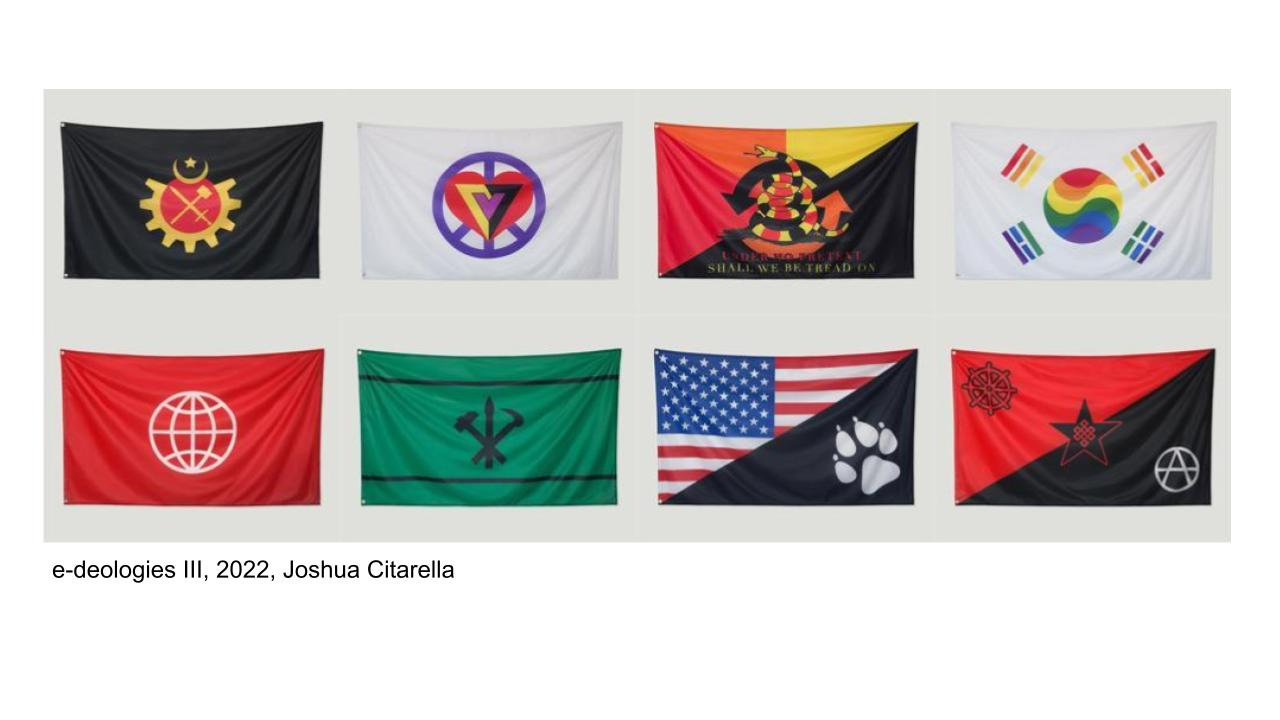

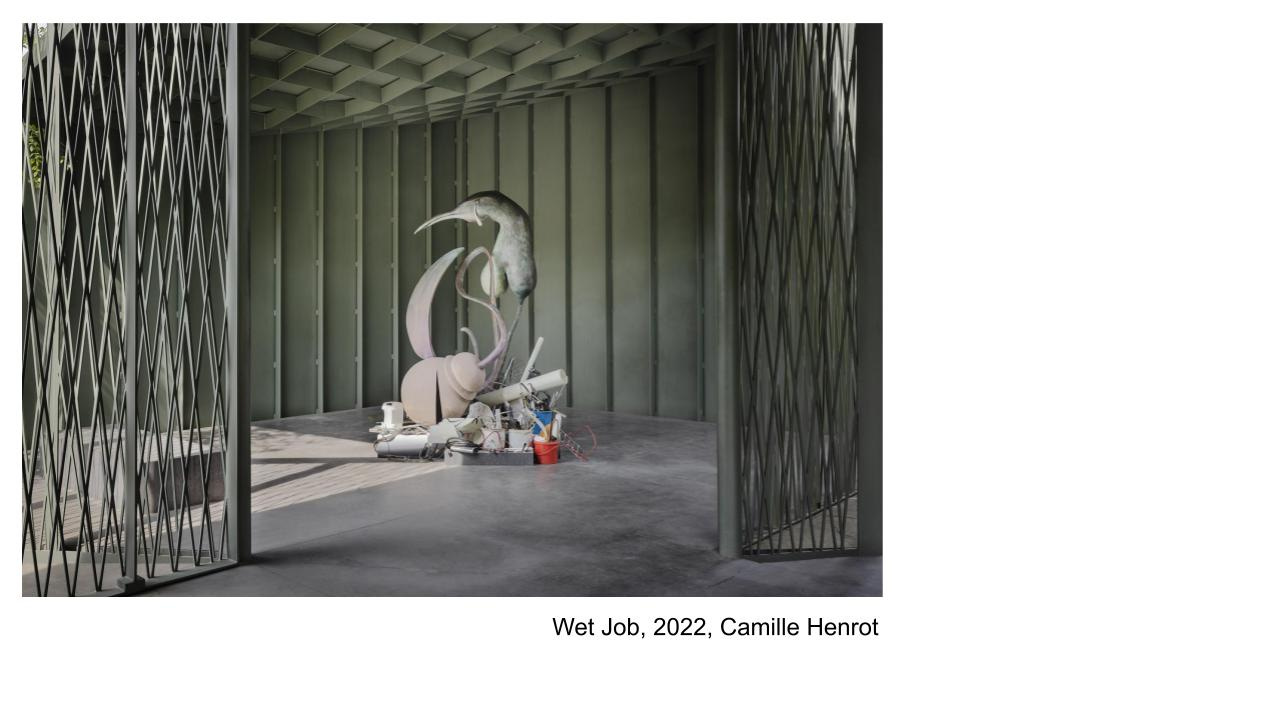

The Post-Internet artists instead leaped from the web, back into the real, smuggling with them the materiality, aesthetics and theoretical essence of the internet and its Irl influence. Gone was the utopian thinking of early web-connoisseurs who fed on diets of DIY ethics and decentralised collaboration, in the post Web 2.0 network of extreme corporate consolidation and state monitoring, there bred a new attitude toward the internet. The Post-Internet attitude is one of playful nihilism, a psycho-sexual comedy of corporate lovecraftian technologies - data extraction, surveillance, commerce and a perverted sense of the self and the world, falling apart or shifting into something unknowable but tantalisingly new.

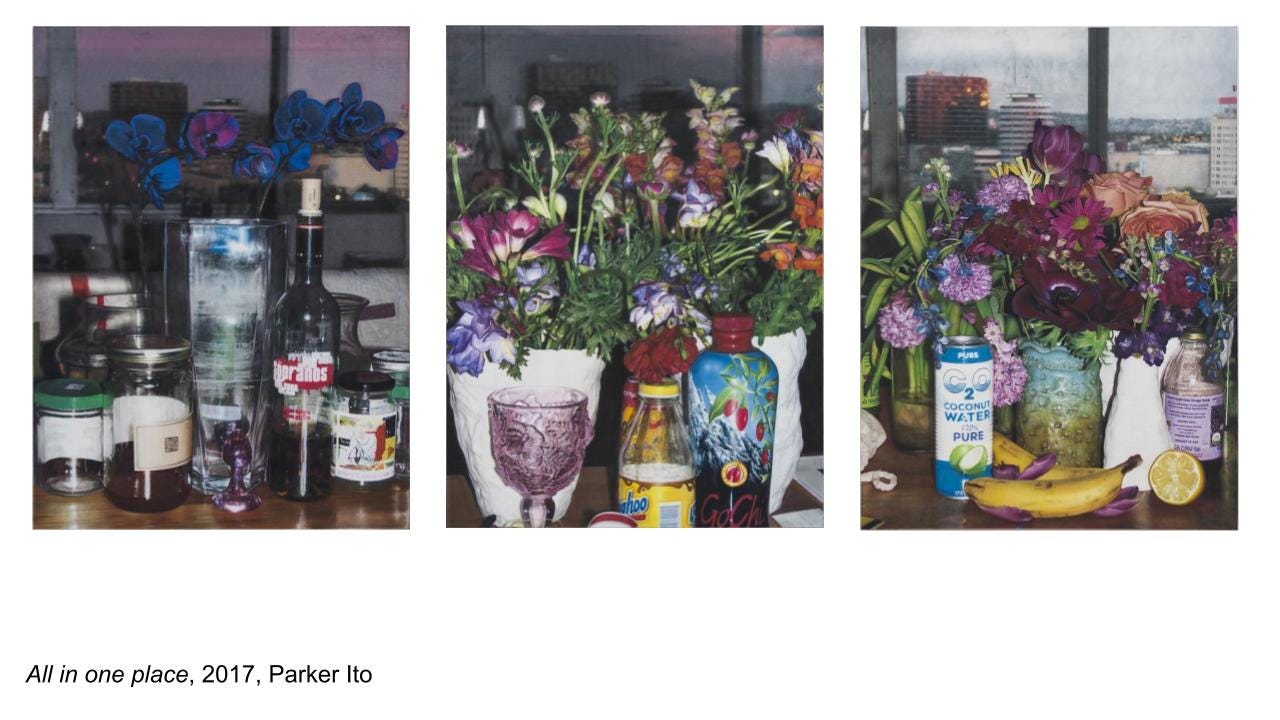

Through appropriations of the visual and material languages of advertising, social media, stock imagery, mass production and corporate branding, Post-internet artists perform interrogations upon the conditions created by globalised networks of trade and communication facilitated by the infrastructural internet. These societal conditions have created myriad knock-on effects, from social media’s atomisation of selfhood into 1000 fluid parts to the recession of the real, a proliferation of signifying information and simulated functions such as e-commerce and ‘virtual praxis’.

The term Post-Internet is widely used to describe the emergence of ‘network minded’ artistic practices but there remains much debate about the efficacy of the term. From insinuations of historical erasure to curatorial meltdowns about the ‘post’ prefix, the term Post-Internet has been the almost-orphan of the art world for many years.

In his essay, Against the Post-Internet, Rafael Lubner argues that,

“by treating the internet as a monumental event that has shaped the entirety of the present, the post-internet, as both a discourse and a concept, gains its particular “currency.” History must be stripped of complexity, ossified and binarized, for the post-internet to function.”

Here, Lubner insists that Post-Internet discourse necessitates a flattening and binarising of histories, an isolation of before and after the internet, an erasure of the political and historical complexities concerning the conception of information networks.

I think Lubner is a fool.

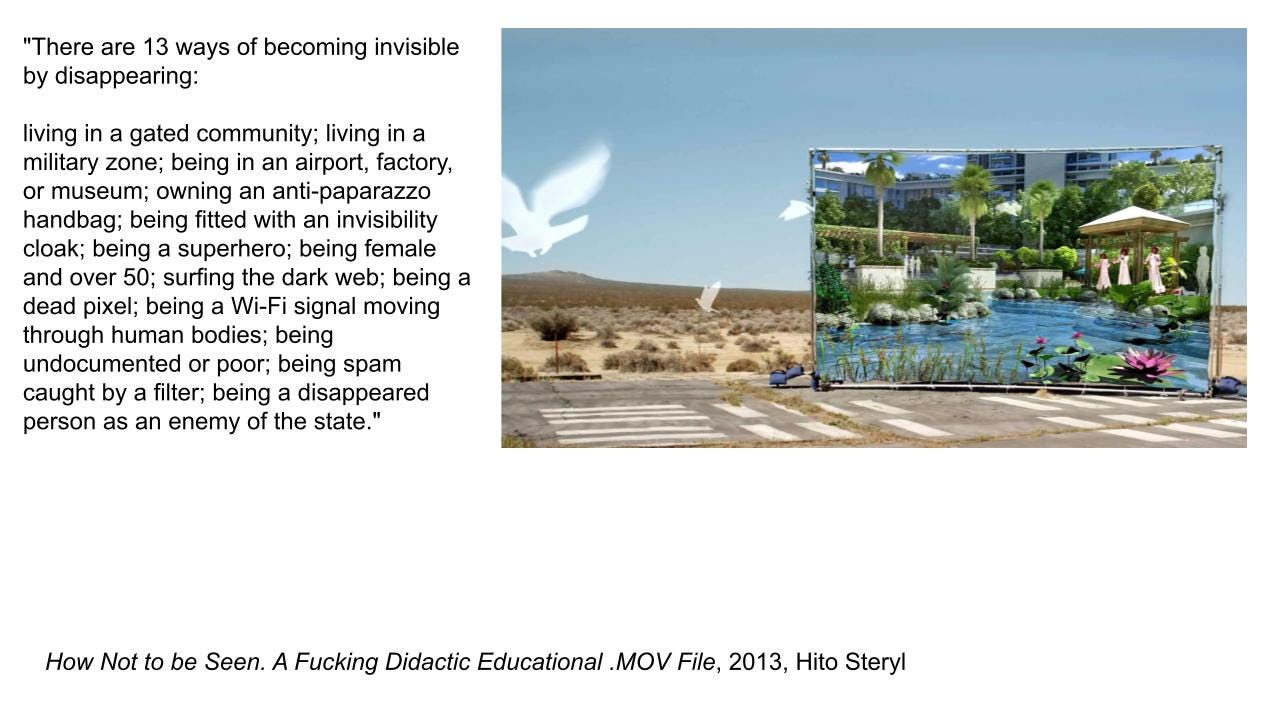

A major conceptual quality of post-internet art is its engagement with myriad cultural and political histories that have come into competition due to networked globalisation. One shining example is Hito Steryl’s, 2013 video-work, How Not To Be Seen. A Fucking Didactic Educational .MOV File.

In this work Steryl traces the complex and competing histories of political visibility via the history of the US military’s development of aerial geographic photography and its ongoing influence in networks of surveillance. How Not To Be Seen illuminates historical and political relations between states of visibility and experiences of gender, class, geo-politics, commerce, violence and digital simulation. Tapping into the density of the internet’s open source information and following a hyperlink-like web of relations, Steryl uses a Post-Internet artistic practice to not only address the historical complexity of her subject but also strengthen these relationships through a structurally Post-Internet presentation of information. While Hubner believes the qualifying ‘post’ of Post-Internet creates a monolithic new history, Steryl and the Post-Internet artists are not lost to the histories that constructed and continue to influence networked society to this day.

This qualifying ‘Post’ in the term Post-Internet has been a point of particular contention.

“How can we be post-internet when internet is still here?”

exclaims curator Brian Droitcour.

Another curator, Christiane Paul decries,

“The most misleading aspect of the suffix “post-” is that it describes a temporal condition but we are by no means after the internet.”

Before arguing that curators are after easy catch-all terms for marketing purposes, I would like to highlight the example of Post-Colonialism. While some surely do believe the era of colonialism is over and we live in a world after colonialism, this is simply not the case. Colonialism has not ended, it has transformed into a subterfuge market dynamic wherein the desires of colonial states are executed via corporate resource extraction and symbolic, not functional sovereignty.

The ‘post’ in Post-Colonialism does not deal in this imagined end of colonialism, it deals with the real ongoing global consequences of colonialist histories and neo-colonialism. The same rule can be applied to the ‘post’ of Post-Internet. It is a discourse concerned not with the unreality of the end or irrelevance or stagnation of our developing networks but with the complex and multi-magnitude outcomes of these technologies. Just as postcolonialism exists as a response to the assertions and conditions propagated by colonialism, Post-Internet discourse exists in response to the assertions and conditions created by the internet. While some theorists may represent these conditions as an extension of industrial modernity or hyper-modernity, I believe these conditions are so inextricably linked to the construction and ubiquity of the globalised internet that they must, for the sake of clarity, be defined as the Post-Internet condition.

This isn’t to say that all contemporary art is necessarily Post-Internet or even engaged in a Post-Internet discourse, though it may help clarify the conceptual qualifications for what we define as Post-Internet art in its critique of the societal fallout of networked systems.

Mark Tribe, Founder of the new media platform Rhizome, posits that

“Post-internet art could be unpacked as “art after the internet,” but in this case after means “in the style of” rather than “later in time.”

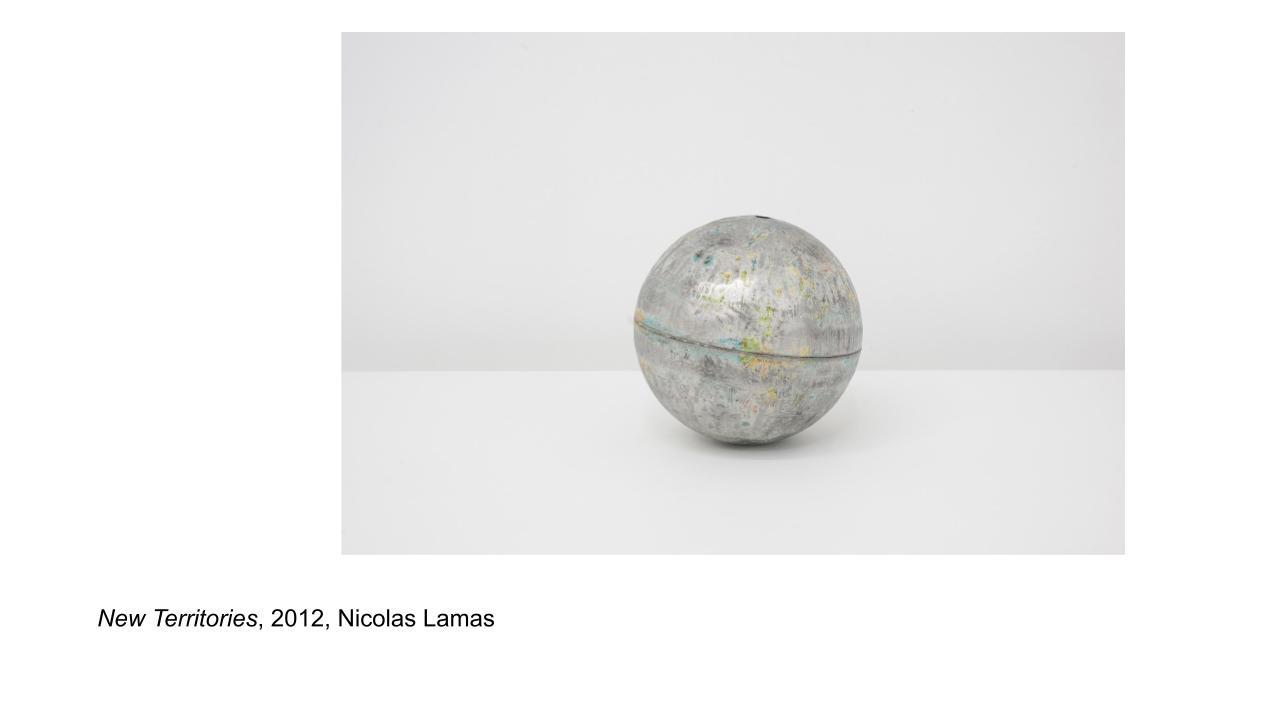

It is risky to disagree with an expert but I can’t help but feel that Tribe’s aesthetic reductionism does an injustice. Post-Internet art certainly does engage with the aesthetic inclinations of the internet - a cacophony of loosely related images, commercially fabricated assemblages and market optimised visuals are common ground for Post Internet artists - though it isn’t as simple as, internet as aesthetic. Post-Internet art as we’ve previously established is a critique of the conditions created by the internet, not solely a replication of its visual qualities. It is a framework which does not rely upon a visual reference to the internet but absolutely must engage with the consequent societal shifts which occurred after the advent of Web 2.0 and the ubiquity of a commercialised internet.

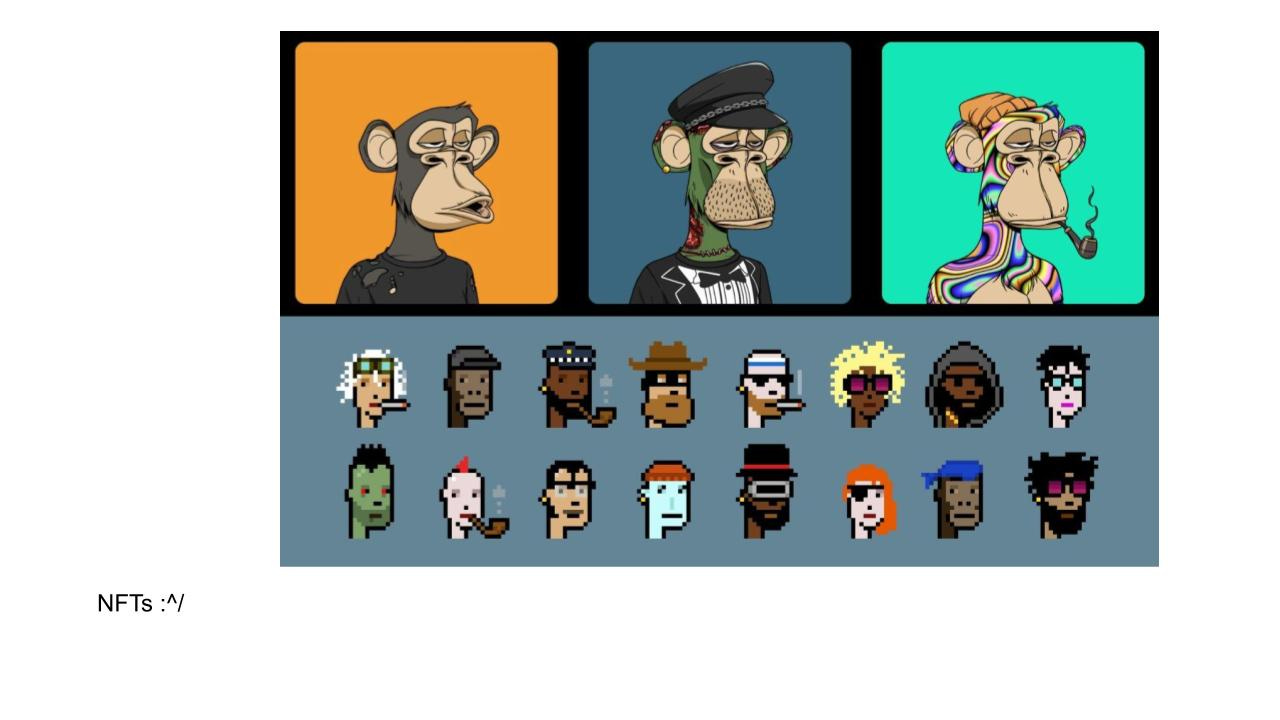

By reducing Post-Internet art to a purely aesthetic expression, we could come to include the logo-esque, generative images of NFTs in a lineage of Post-Internet art or amalgamate the web-based content of Net.Art into the Post-Internet cannon. This would miss the qualifying intent of Post-Internet artists, as theorists of a networked societal condition.

It is my firm belief that the term Post-Internet is a sufficient and articulate label for artists who as Eva Folks of AQNB puts it

“are so deeply embedded in and propelled by the internet that the notion of a world or culture without or outside it becomes increasingly unimaginable, impossible.”

To be Post-Internet is not to forgo a pre-internet history, advance beyond the influence of the internet or mimic its aesthetic inventions but to inhabit, channel and critique the societal conditions which our networked superstructures have created.